Opera del Duomo Museum

The Museo dell’Opera del Duomo opened in Pisa in 1986 under the guidance of Guglielmo De Angelis d’Ossat. It was not entirely new, because in 1935 the small loggia and two other rooms in the Palazzo dell’Opera had housed a small collection of sculptures and stone fragments, curated by the young art historian Enzo Carli. But the new museum was an authentic revolution for the wealth of materials collected, for the decision to give the collection an entire building in the Piazza del Duomo, which had just been left free by the religious community that lived there, for the rationality of the display installation, for the important scientific discoveries, and for the meticulous preparations carried out by a valiant team of scholars. At this point, one might wonder why any more work should be needed on such an important museum. The answer is quite simply that museums are like trees, for which the passing of time involves the shedding of leaves and the growth of the entire plant. Metaphors aside, what we have here is a museum from thirty-three years ago enriched with important new items, stripped of some excesses, and with a redesigned display installation that shows off the original value of the works to their best advantage.

Visitors who recall the previous display will no longer find some objects, or groups of objects, which are now in different exhibition spaces or in rationally organised storage areas open to scholars. The most conspicuous places are the scale models of buildings in the Piazza, the archaeological collection, and the modern paintings. With the partial exception of the paintings, these materials were not directly linked to the Cathedral or the other buildings, nor to the primary religious function of these edifices. Their exclusion thus makes for a clearer understanding of the exhibits, as well as of the individual works already in the museum or newly added to it.

The visit starts in solemn style on the ground floor, with the Bonanno Door. This is followed by a gallery devoted to the Cathedral in the Romanesque age, with marbles from the façade and interior furnishings. After dwelling on some artefacts from overseas, which are very important for understanding Pisan art of that period, the tour continues with the Baptistery and its Gothic sculptures. The hand of Nicola de Apulia, which is very evident in the heads and half-lengths in the Deesis, here gives way to the superb full-length figures by his son Giovanni, who comes to the fore in the next two galleries. First, in his portraits and in the fabulous bestiary of the gradule, and then in the splendid groups of the Virgin and Child with various other figures. In all these cases, it was only necessary to examine the quality of the sculptures and their place in the architecture to give visitors the best possible experience. This proved to be especially true in the gallery devoted to Giovanni’s followers – Tino di Camaino and Lupo di Francesco – and in the one with Andrea and Nino Pisano, in which the addition of some important, and voluminous, masterpieces has given new value also to the existing ones. Continuing along the way, it is not hard to see that, during the period of the Renaissance, the hallmarks of Pisan art give way to those of Florence, also in terms of marble sculpture. In the gallery devoted to the Tower, the group of half-length figures by the Florentine Andrea Guardi introduces the style of Donatello to one of the greatest masterpieces of medieval architecture, interacting with what remains of an arabesque tarsia and a stunning Romanesque capital. While the works of the masters we have seen so far mainly come from the exteriors of the buildings, the last gallery on the ground floor contains a sacred interior, in which Mannerist marbles and bronzes pay tribute to the early fifteenth-century painted wooden Crucifix that heralds the works on show on the upper floor.

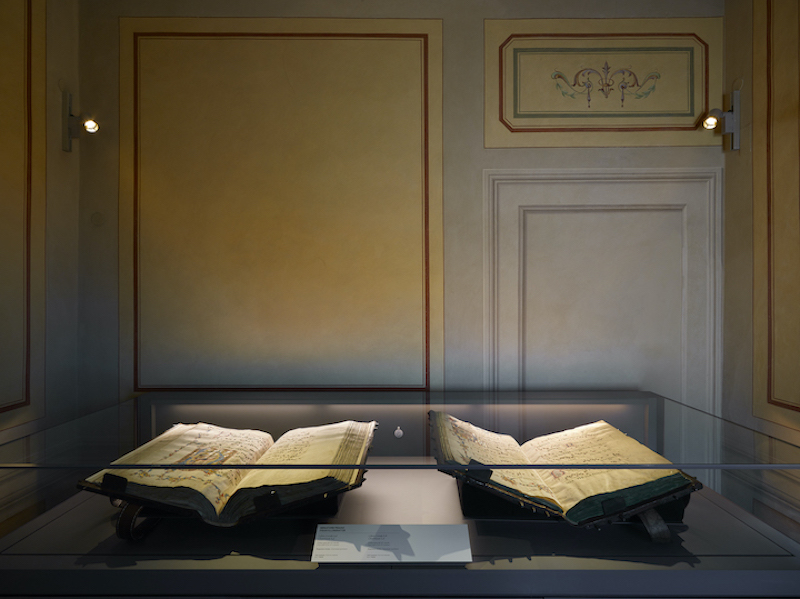

For the practice of worship, a sacred Christian building needs liturgical furnishings, images, vestments, vessels, and books. At the top of the staircase, visitors are greeted by the wooden choir of the Cathedral. These are intaglio and marquetry pieces designed for the clergy as they pray together. The images, on the other hand, appear in the next gallery. The carved Romanesque Christ was part of the previous display, while the painting by Spinello Aretino opposite it is a new entry, which well captures the importance of painting in the late Middle Ages. These monumental images are accompanied by two Limoges reliquaries, the beauty of which becomes even more precious in the small masterpieces made by Giovanni Pisano and other masters in the next gallery. Further on, the textiles and goldwork gathered around the funeral shroud and insignia of Emperor Henry VII – another important new feature in the display – illustrate the key role played by these techniques in the art of the past. Not coincidentally, we now find three galleries devoted to liturgical vestments and another three to sacred vessels. Visitors can see with their own eyes the variety of solutions and techniques that named and anonymous artists were able to adopt in only apparently serial productions. These spaces are connected with those that house liturgical books – both the extremely rare rolls of the Exultet and the more common altar and choir codices. Since only part of this vast collection of extremely delicate materials can be shown, modern technologies are used to satisfy the needs of the most demanding visitors by unrolling the Exultets and making it possible to turn the pages of the codices.

However, the museum does not end here. Once out in the loggia, the visitor has a splendid view of the Tower before going down to the ground floor to see one last magnificent manifestation of Pisan sculpture at its finest in the cloister. Some colossal busts that once crowned the Baptistery are aligned along the left-hand wall in bays that suggest the intense interaction between these statues and the architecture. They were made by the young Giovanni Pisano, who has appeared many times, making him the absolute protagonist of this museum.

Award-winning for the new layout

In 2021, as part of the Festa dell’Architetto at the Venice Biennale, the museum was ranked first in the category “Set-up or Interior Works” for the project by the Guicciardini & Magni Architetti studio in Florence, which oversaw the new layout in 2019.